When I heard of this issue’s topic, I was immediately reminded of a time before I was a teacher, when I was working in retail. If you have also worked retail or in the food industry, then you will remember working with customers who were lovely, and customers who were let’s say… difficult. Especially with understanding coupons. In those situations with difficult customers, how were you emotionally? For me, I learned to suppress the emotions I was feeling in the moment. After suppressing negative experiences with customers many times, it got to me and my job became increasingly difficult to manage. The thing is, I carried this particular strategy with me to the teaching position I have now. There are days where I have challenges in my personal life, but I cannot and will not take those emotions into my classroom. Other days, there are particular classes that don’t go well, but I have to carry on and suppress what I am feeling during that class. The act of suppressing your emotions is actually one of the two common emotional regulation responses, and I think many people have had some kind of experience with it. However, as we saw with my story above, suppressing emotions is not a particularly good strategy to have. So, allow me to go over the details of emotional regulation, how it affects teachers and students, and a few better strategies that may help in regulating emotions in the future.

The details of emotional regulation

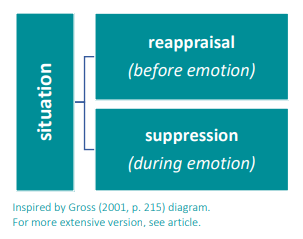

Gross (2001) found that emotional regulation is both the conscious and unconscious strategies humans use to increase, maintain, or decrease an emotional response. The example he gives is if a car cuts in front of you while you’re driving, you don’t go and purposefully crash into said car; you regulate your emotions to produce a better, more appropriate reaction. Basically, you are trying to control your emotions when a situation arises. As I wrote earlier, there are two common strategies of emotional regulation, one being suppression, and the other, reappraisal. The difference between the two is that reappraisal is used when we respond before an emotion or situation, which is basically you predetermining your reaction to a situation or emotion (good or bad) before you go into it, and suppression is what we do while the emotion or situation is in progress, or reacting to something (Gross, 2001).

What is interesting about this is that suppression actually takes more energy physiologically because you are trying to self-monitor and self-correct continuously, which can lead to memory loss and high blood pressure (Gross, 2001). Reappraisals, however, require less energy because you are not putting in as much or any self-regulatory effort (Gross, 2001). Now, we can see the benefit of reappraisals here, but another study found that the benefits of reappraisals do depend on the context in which they are used. In particular, when people are in situations they can control, reappraisals may show no change to improving their mental health because they could use problem-solving strategies instead (Troy et al., 2013). When people are in situations they cannot control, reappraisals work better in helping them to come to terms with their situation (Troy et al., 2013). Therefore, it does depend on the individual and their situation whether reappraisals are beneficial or not. However, I would argue that anyone working with people, as teachers do with students, will always have to deal with some kind of uncontrollable event or situation.

Emotional regulation for students vs. teachers

Students and teachers have a tendency to mirror each other’s emotions in the classroom. When students are undisciplined or acting up in class, it increases the teacher’s anger and anxiety (Hagenauer et al., 2015). Then, when students feel their teachers are not providing them with emotional safety, they lose engagement and trust in class (Arguedas et al., 2016). It ends up creating a vicious circle. This is why emotional regulation is important to teach to both students and teachers. They both can continually learn skills to support and control their own emotions using regulation strategies. But, emotional awareness is involved, too. In Arguedas et al.’s (2016) study, they found that students with high emotional awareness had higher levels of motivation to complete a project, and maintained their motivation even when they got bored or sad. Students were also more cooperative with their peers, and changed or adapted their behaviors to what benefited the group. It was also Arguedas et al.’s (2016) study that found that students with low emotional awareness levels were more likely to feel their teachers were not as supportive to them as the teachers were to other groups when they encountered difficulties.

While Arguedas et al.’s study did not note how the students behaved towards their teachers, I would say, based on my own personal experience, students tend to put in less effort when they do not feel supported by their teacher. This can make it frustrating for the teacher. That cause-effect relationship is what Hagenauer et al. (2015) found in their study. They showed that student behavior tends to predict a teacher’s emotions: when students behaved well in class, the teachers experienced joy, and when they did not behave in class, teachers experienced anger or frustration. However, both of these emotional responses were affected by two things: how long the teacher had been teaching, and the quality of their interpersonal relationships with their students (Hagenauer et al., 2015). They noted that experienced teachers had more knowledge of strategies to use with students compared to new teachers, and those with closer and more positive student-teacher relationships experienced the most joy out of all the teachers in the study. They went on to state that for teachers to have more positive interpersonal relationships, they need to be taught how to develop their own socio-emotional competencies, which include emotional awareness and regulation strategies (Hagenauer et al., 2015).

Emotional regulation strategies

The two studies above did not suggest any particular strategies for developing emotional regulation, but I have a few ideas that may be useful for you! Keep in mind, these are just suggestions, and you may find that they do not fit your exact needs. That is okay though; think of this part as a starting point to research more deeply into activities that work for you. The strategies I did find actually work great for both teachers and students, so feel free to adapt where necessary!

The very first step in emotional regulation is to clearly communicate what emotion you are feeling. So, the first thing I want to talk about is The Feelings Wheel by Dr. Gloria Willcox (Calm, n.d.). If you’re like me, you may not be able to clearly identify what you’re feeling when you’re caught up in the moment. The Feelings Wheel helps with that. The innermost circle is all your primary emotions: sadness, happiness, etc. You move one ring outward, and you get into the secondary emotions, which are a little more specific. The final outward ring shows your tertiary emotions, which are the most specific. When you have a better understanding of what exactly you are feeling, it will be easier for you to communicate exactly what you need. I have heard of adults using this in therapy to help work through their struggles, and I have also heard of teachers posting this wheel in their classroom for their students to use. You can get creative with how you want to implement the wheel, I personally have a copy in my office posted for myself and any students who might come in to talk.

Once you have your emotion identified, the next thing you can work on is accepting that emotion and letting it go (Ackerman, 2018; Klynn, 2021), which is a form of reappraisal. Some people tend to run away from their emotions, but accepting them involves recognizing that they are valid and natural. When you stop running away from your emotions, it helps you realize that the main issue causing those feelings can be more manageable than you realize (Ackerman, 2018). Accepting emotions also involves practicing mindfulness and self-compassion (Klynn, 2021), and I actually talked about some strategies for this back in our Care issue in December! But, for time’s sake, I’ll give one of many examples, which is using mindfulness to take note of your feelings and senses throughout the day in a non-judgemental way. That’s the key. You can write a short reflection after your work day about the emotions you felt and what brought about those emotions. This can also be adapted so your students reflect on their days too. There are also a lot of self-compassion activities, but the end goal is to be kinder to yourself. How I like to do that is by saying a little mantra at the end of the day: “I did the best I could today and tomorrow will be a new day.” Anything like that works, as long as you are allowing yourself to recognize that mistakes can happen, but you don’t need to be so hard on yourself.

Accepting and letting emotions go is definitely easier said than done. Sometimes in a moment of anger and frustration (for example), you may not be able to control your emotions. So, I have two final suggestions for just this case. The first is to remember that you have a choice in how you respond. Instead of going with your first reaction, take a step back and consider if there is a second path available (Klynn, 2018). You can also get curious about both your responses and the responses of anyone else you may be speaking with by asking questions to yourself (Klynn, 2018). For example: “Why did I react this way?” “Is there something deeper going on?” “How did they react?” “Why did they react that way?” When you stop to ask yourself questions, it takes you out of the moment of reactivity and brings you back to dealing with the bigger issue.

The second suggestion is a technique called STOPP created by C. Vivyan in 2015. STOPP stands for Stop (pause), Take a breath, Observe (What are your thoughts right now? What are you reacting to?), Pull back (What’s the big picture here?), and Practice what works (What can you do right now that’s best for you?) (Ackerman, 2021). For the full list of questions, take a look at the link above (Use the find function with the keyword “stopp” as it is not at the top of the webpage). The second strategy here overlaps the first strategy I mentioned (thinking of your choice of responses), but has a few extra steps. STOPP is great if you are already past being able to reappraise your situation and you need an easy strategy to remember to soften your emotional response. I also think STOPP would work really well with younger students, to help them in remembering to regulate when they get upset.

As we can see, there are a lot of options and avenues that you and your students can take to reach a higher level of emotional regulation. But, just keep in mind that while these strategies are great, it may just happen that they all fly out the window during a particularly stressful situation. And that is totally okay because no one is perfect, and your feelings are valid. However, I think if you can adapt to the different stressors of teaching—and you can handle the customer who came into your store to yell at you because they didn’t understand the stipulations of their coupon (real story from retail days!)—then you have the ability to reappraise your emotions the best way you can, which will help you and the people around you feel more calm and connected to each other.

References

Ackerman, C. E. (2018, February 5). 21 Emotional Regulation Worksheets and Strategies. PositivePsychology.com https://positivepsychology.com/emotion-regulation-worksheets-strategies-dbt-skills/#hero-single

Arguedas, M., Daradoumis, T., & Xhafa, F. (2016). Analyzing how emotion awareness influences students’ motivation, engagement, self-regulation and learning outcome. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 19(2), 87–103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.19.2.87

Calm. (n.d.). The Feelings Wheel: Unlock the power of your emotions. https://www.calm.com/blog/the-feelings-wheel

Gross, J. J. (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 214–219. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182746

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., & Volet, S. E. (2015). Teacher emotions in the classroom: Associations with students’ engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(4), 385–403. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24763247

Klynn, B. (2021, June 22). Emotional regulation: Skills, exercises, and strategies. BetterUp. https://www.betterup.com/blog/emotional-regulation-skills

Troy, A. S., Shallcross, A. J., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2505–2514. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24539341

Kate Piatkowski is a language instructor at the University of Hyogo. She has been teaching ESL for the past eight years in both South Korea and Japan. She enjoys researching topics related to Social and Emotional Learning and figuring out how both teachers and students can improve their mental well-being.